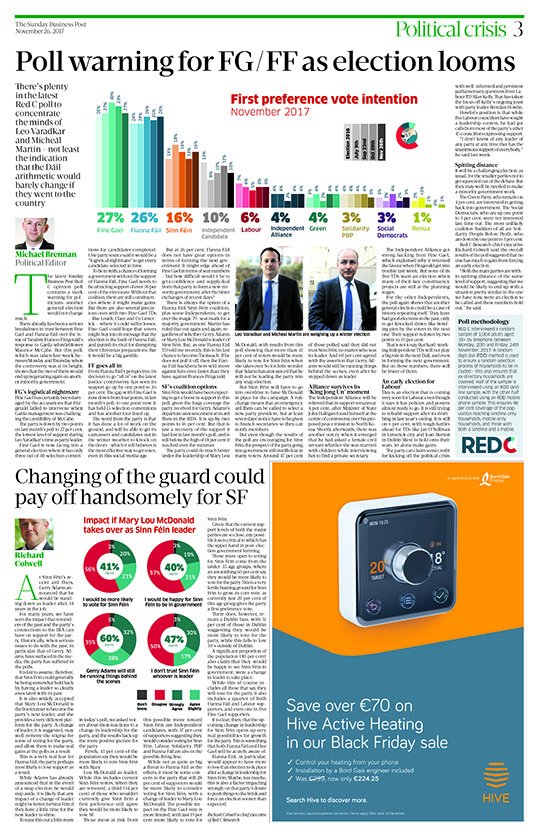

As a starting point in any general election campaign, a Taoiseach whose party has lost two percentage points and has just over one quarter of voters’ support, is in a very poor place indeed. Still more worrying is a poll finding that you are within one percent (or the margin of error) of the support level for your chief rival, Fianna Fáil. But that is the bleak landscape revealed in today’s Sunday Business Post Red C poll.

If we hoped to escape from the political paralysis of the “new politics”, the fact that Fine Gael and Fianna Fáil, parties without a hair’s breadth of ideological difference, enjoy only 27% and 26% support respectively strongly suggests that neither party can reasonably hope to govern without a confidence and supply agreement from the other.

And if the issue that caused the general election is the continued tenure of a member of the outgoing government who held office by virtue of that confidence and supply agreement, the question must arise as to whether that issue could be in any way resolved by an outcome which required yet another confidence and supply agreement between the same two parties.

How could an election triggered by that issue resolve the issue in any way? Presumably the Tánaiste would seek re-election. How could Fianna Fáil credibly enter into a confidence and supply agreement with Fine Gael if she were to remain Tánaiste? What, then, would the election have been all about?

All this suggests that a general election will not lead to a radically different political landscape. Given our problems in relation to Brexit, the housing crisis, homelessness and the health service, it is very difficult to see how a mad winter dash to the polls could deal with these problems any way differently from what is happening, or more likely, not happening at the moment.

Is there also a sense in which an early election would neatly sidestep the looming controversy over the 8th Amendment by dissolving the all-party committee due to report in the next few weeks? Some cynics might think that the Taoiseach would like to have a general election before the Fine Gael monolith explodes in a cloud of liberal and conservative shards on the abortion issue.

The Finance Bill, which is a money bill, must now be sent to Seanad Éireann within 21 days. Dáil Éireann passed it on Thursday the 23rd of November. If Seanad Éireann were to make any recommendation in respect of the Finance Bill, and if Dáil Éireann had been dissolved within those 21 days, the Finance Bill would lapse with the dissolved Dáil. Likewise, the Social Welfare Bill can hardly now be enacted in the context of a dissolution of Dáil Éireann.

For all these reasons, a pre-Christmas general election has always looked very unattractive.

From a party political point of view, pressing the flesh and leading the party faithful on canvassing expeditions at the height of the festive season is likewise highly unattractive. Voters’ minds will be focused on other issues and politicking will be seen as an annoyance especially if the electorate comes to the conclusion that the only likely outcome is more of the same.

The mini-crisis over the Tánaiste, while important in terms of accountability of the executive to Dáil Éireann, is unimportant in terms of the challenges which our government and our parliament face anyway.

To take one example – the Brexit issue – it was strange indeed that a deeply damaging leak this week of the Department of Foreign Affairs report on its Brexit related diplomatic activity has not loomed larger in media discourse.

In whose interest was it to leak the document? The answer to that question is most likely to be found in the probable consequences of the leak. Those consequences are very damaging indeed.

What European minister, diplomat or office holder is going to engage in discussion with Irish diplomats on the issue of Brexit if their opinions are likely to be reported verbatim in the public media?

Whoever leaked the Foreign Affair’s memorandum can only have done so to sabotage Ireland’s capacity to pursue a diplomatic campaign among the member states in pursuit of our Brexit related objectives.

It is possible that the leak was purely accidental, of course. But if it was deliberate, the leaker might well have been someone in the neighbouring jurisdiction with the intelligence capacity to obtain and disseminate what was intended to be a confidential document.

If you wanted badly to weaken Ireland’s capacity to influence the outcome of the first phase of the Brexit negotiations in relation to the Irish border, you could think of no better way to do so than by making it dangerous for our 26 remaining fellow member states to engage with Ireland on the issue at all. Perfidious Albion may be innocent in this matter but, then again, it may not.

Regardless of whether Ireland has been the victim of dirty tricks or of its own incompetence, the forthcoming European Summit dealing with Brexit is an occasion on which we do not need to be represented by a lame duck “acting Taoiseach” leading a lame duck “acting cabinet”. That consideration is yet another reason why a futile general election should be avoided.

Underlying much of the present political impasse is the continuing failure of those who hold executive office in Ireland, whether they are elected or unelected, to be accountable to Dáil Éireann for the exercise of the executive power of the State for which the government is, by Article 28.4.1 “responsible to Dáil Éireann”.

While commissions of investigation and tribunals of inquiry may properly be established to investigate matters of public importance in an impartial way, that does not mean, and has never meant, that the establishment of such an inquiry has the effect of putting accountability of the executive power of the state to Dáil Éireann in suspension while such inquiries are continuing.

To take one example, the circumstances under which former Commissioner Martin Callanan came to resign his office became the subject of a commission of investigation which resulted in the Fennelly Report. That report was unable to resolve serious conflicts of evidence between some of the dramatis personae. But the establishment of that commission of investigation was given as the reason why factual questions on the issue could not be answered in Dáil Éireann or any of its committees.

The true and proper interpretation of the Constitution is that the Dáil’s entitlement to have parliamentary questions answered truthfully and properly is not in any way abrogated or frozen or postponed by a decision to establish a statutory inquiry covering the same territory. Telling the simple truth to the Dáil in no way compromises or prejudices the proceedings of a statutory inquiry tasked to deal with the same issue.

Here’s hoping that our politicians have the sense and perspective to avoid an untimely and futile electoral battle between themselves – when the people are looking to them to unite in finding real solutions for our very difficult but soluble problems.

It was once wisely remarked that “war does not decide who is right, but only who is left”. The same applies to any general election triggered now by a dispute which it cannot resolve.