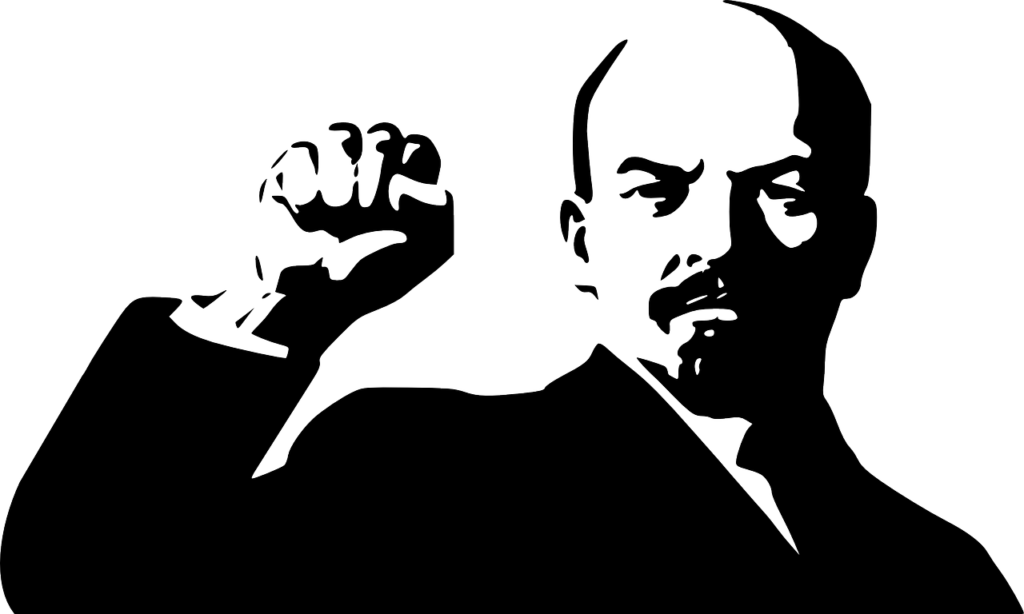

I was intrigued to see posters featuring Vladimir Lenin and red flags featuring the hammer and sickle in evidence at a recent counterdemonstration in support of transgender rights at Merrion Square. This counterdemonstration apparently aimed to drown out by noise a demonstration organised by a group called Let Women Speak, which featured a controversial UK feminist anti-transgender speaker Kellie-Jay Keen, otherwise known as Posie Parker.

Members of An Garda Siochána erected crowd control barriers to prevent any unwarranted interactions between the two demonstrations and the events apparently passed off peacefully – if noisily on the part of the counter-demonstrators. It was a wet weekend; only committed enthusiasts – men and women – came to take part.

Images of Lenin and the hammer-and-sickle red flag of the Bolshevik revolution visible in social media postings about the event are nonetheless intriguing. I had noticed a hammer-and-sickle logo on a banner briefly hung on the Ha’penny Bridge during Gay Pride Week.

That there are still ardent Leninists campaigning in the Irish political sphere should not surprise keen students of contemporary Irish fringe politics. To quote Gerry Adams: “They haven’t gone away, you know.”

Paul Murphy TD left the Socialist Party to form Rise, which subsequently joined People Before Profit. Back in 2019, he participated in vigorous internal debate in the Socialist Party, which was extensively covered by The Irish Times, and which featured the application of Lenin’s political dogma to the party’s approach to the European Union.

While People Before Profit, a party with four TDs, rejects the term Trotskyist, that is the usual description of the party’s position on the hard left of the political spectrum. It recently published a pamphlet on the need for a left-wing Government including itself and Sinn Féin, a document which I thoroughly recommend; great value at €3 because it sets out the agenda for a socialist coalition after the next election.

A point that people may ponder is why any group of modern politicians or human rights activists in Ireland would seek to identify with Lenin, a century after his death. While it is true that the Bolsheviks briefly allowed sexual liberation in the years following the 1917 Russian Revolution, that didn’t last.

Even though male homosexual activity was decriminalised in the early years of the Soviet state, it was formally re-criminalised by Stalin in 1934 after a period in which it had become increasingly repressed as evidence of “bourgeois decadence”.

It is an irony that it took Boris Yeltsin to decriminalise male homosexuality again. Last year, Vladimir Putin signed into law a measure that effectively drives underground public discourse on LGBT+ issues because it undermines what he sees as traditional Russian values.

The real problem with fetishising Lenin is his personal addiction to mass execution of political opponents. His period in charge of Bolshevik Russia was marked with the first use of mass political extermination of political or class enemies in modern times.

Cruelties of political executions in Tsarist Russia fade into numerical insignificance when compared with Lenin’s state murder, which, it is widely thought, took the lives of 100,000 – leaving aside his ruthless instruction to kill kulaks who resisted collectivisation.

Lenin is no model or icon for Irish human rights activists. He had no time for civil liberties or bourgeois democracy. He had no time for freedom of expression for political opponents.

Lenin was personal progenitor of totalitarian politics in the 20th century. The very phrase “liquidation” when describing murder of political opponents was first used by the Leninists with the Russian term “likvidirovat”.

Lenin and his successors in the communist International were but the first in the 20th century to practise and justify mass political liquidation of opponents. That is his odious legacy.

Before Lenin, mass political extermination of ideological enemies as later practised in Stalinist Russia, Nazi Germany and civil-war Spain had been generally unknown in the 19th century. Revulsion at the great terror unleashed by the French revolutionaries (in which 17,000 perished by execution) had been almost universal.

The other legacy of Lenin is the political tactic of eliminating middle-ground politics. Leninists crave, and thrive on, deeply polarised politics as precursors to revolution. The collapse of the Weimar Republic in a contest between Reds and Nazis is but one example of how Lenin’s political theory works out in practice.

That is why some in the Irish hard left now welcome the idea of an Irish hard right and the opportunity it gives them for street politics – and to wave Lenin placards and hammers and sickles.

Resolving matters of free speech, hate speech or gender ideology is not something that should be weaponised – or decided by the infantile street politics of the hard left or hard right. These issues are too important for that.