Instead of tabling a motion of no confidence in the Housing Minister, the member of Dáil Éireann would be far better employed establishing a forum on the future of Dublin – a forum which would consider how the city of Dublin and the neighbouring counties are to be governed in future, a forum which would look at the likely growth prospects for Dublin, and a forum which would ask itself a fundamental question – namely whether we can trust market forces and serendipity to shape the future of Ireland’s capital.

Ireland’s system of local government is, in reality, a sham. Local prefects, appointed from the centre and accountable in the last analysis to the centre, make all the major decisions on how their areas are administered and planned. While we have a veneer of democracy in the form of local elections held every five years, the councillors that we elect have very little power, individually or collectively. Such little power as they have is constantly under threat. We need only remember the recent failed attempt by central government to direct local councillors not to discuss individual planning applications in their areas to understand just how tight the grip of the Customs House is on what happens at local authority level.

In England, local authorities have planning committees consisting of elected councillors which consider applications for planning permission and conduct their proceedings in public. In Ireland, by contrast, the planning process is entirely closed and local representatives are denied any formal role.

While it is true that local authority members have an influence over the county or city development plans for their areas, that role is itself a limited one and the real influence of local politicians on the outcome of county development plans is far less than might appear from the planning legislation.

Dublin needs to have a single mayor instead of four county managers and four council chairmen with a one year mandate. While central government might well fear the potential power which an elected mayor of Dublin might wield, the truth is that we badly need some means of political responsibility and accountability in respect of the future development of Dublin.

It seems almost so crazy as to be unbelievable. But €170 million has been spent planning a metro link project for Dublin before a public consultation process as to whether it should be built at all is conducted. Needless to say there has been no detailed cost benefit analysis study carried out on this project. The ultimate cost is likely to be between €3.5 billion and €4.5 billion.

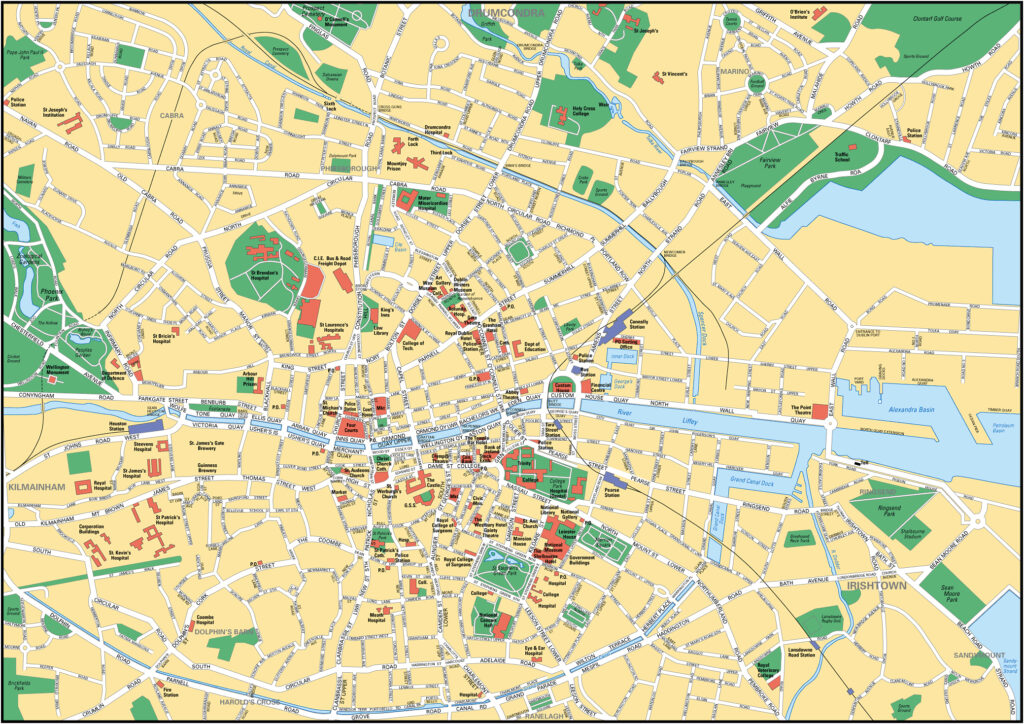

The project entails the construction of a metro light rail system from Swords to Ranelagh, partly surface and partly underground. From Ranelagh to Sandyford, the project involves the cannibalisation of the existing Luas Green line. It probably involves the closure of the Luas Green line between Ranelagh and Sandyford for between 12 and 24 months during construction. The result will be that instead of travelling, as one can now, on a Luas tram from Brides Glen the whole way to Broombridge at Cabra, a person will have to make two separate tram journeys and a metro train journey in future.

Far more important than the destruction of the Luas Green line as it currently exists is the realisation that the cross city Luas line recently built at a cost of €368 million will become an inconvenient and difficult to explain spur added of the metro link system.

Of course, deciding to spend between €3.5 billion and €4.5 billion on the metro link project carries with it a decision (never spoken) to abandon all ambitions for any further Luas tram lines in the greater Dublin area for the next 20 years. Suburbs such as Lucan, Terenure, and Ballybrack on the south side and their equivalents on the north side will, we are led to believe, now be the beneficiaries of a network of super bus lanes to be built along major arterial traffic routes.

While the politicians bicker over who should be Housing Minister, the real questions which face our elected representatives as to how we will remedy our housing crisis go unanswered.

In truth, we have to reimagine Dublin. It cannot continue to grow as a low-rise sprawl. We need to build a huge number of high quality apartments in the city centre and inner suburbs.

I passionately believe that a redevelopment agency with powers to CPO lands, to assemble sites, and to grant building leases of major developments is the way forward.

The property market is left entirely to private enterprise as things stand. Local authorities play little or no role in the positive planning of development in their areas. If we want to have large scale apartment developments such as the one currently under construction at Charlemont Street, we simply cannot confine such projects to areas of public land which have become run down or derelict or under-used.

There are many, many areas of Dublin where the housing density is so low as to make it impossible for individual builders to develop new apartment buildings on lands which may or may not become available for purchase in one way or another over time. In the mid 18th century, the Irish parliament established a body known as the Dublin Wide Streets Commission which re-imagined the city, acquired lands, reconfigured the street layout and granted builders building leases of a much greater density and to a standard pattern so as to dramatically alter the face of Dublin.

Site assembly is a slow and tedious process as we all know. It is made even slower when rival developers play chess with small handkerchief sites so as to stymie each other’s projects or to extract “blackmail” money to buy them out. Perfecting title to the component areas of large development sites is costly and difficult. Giving such development powers to an agency which can, by stipulating building standards and designs, guarantee pleasing and sympathetic street designs, has shown itself in the past to be the way forward. The real problem is that we are wedded to a deeply conservative laisse-faire process of urban renewal which plays into the hands of those who hoard land in the knowledge that its value will continue to grow even if it is under-used.

Some people wrongly claim that the Constitution is a problem and that property rights as protected in the Constitution are an obstacle to the kind of planning and development process that I am describing. But the Constitution is very clear; property rights ought , in civil society, to be regulated by the principles of social justice and the exercise of property rights can be delimited by law to achieving “the exigencies of the common good”.

So the Constitution does not stand between us and the vision of a new and better Dublin.

Failure to radically re-think the housing market in conjunction with transport policies, infrastructural investment and energy policy is not an option that Ireland can afford. The fruits of the continuing failure of present policy which is agitating the minds of the public are rising house prices, diminishing levels of home ownership, increasing dependency on large-scale commercial landlordism and the rapid ending of the aim of owning your own home for the younger generation and for generations to come.

Things cannot go on as they are. Squabbles over front gardens and bus lanes are petty compared to the enormity of the price of our inactivity and our political indolence.