Ireland’s political and diplomatic establishment spent a considerable amount of time, effort and money securing a seat at the United Nations Security Council. To what end?

Do we wish, as a small state, to have our viewpoint and values heard at the top table?

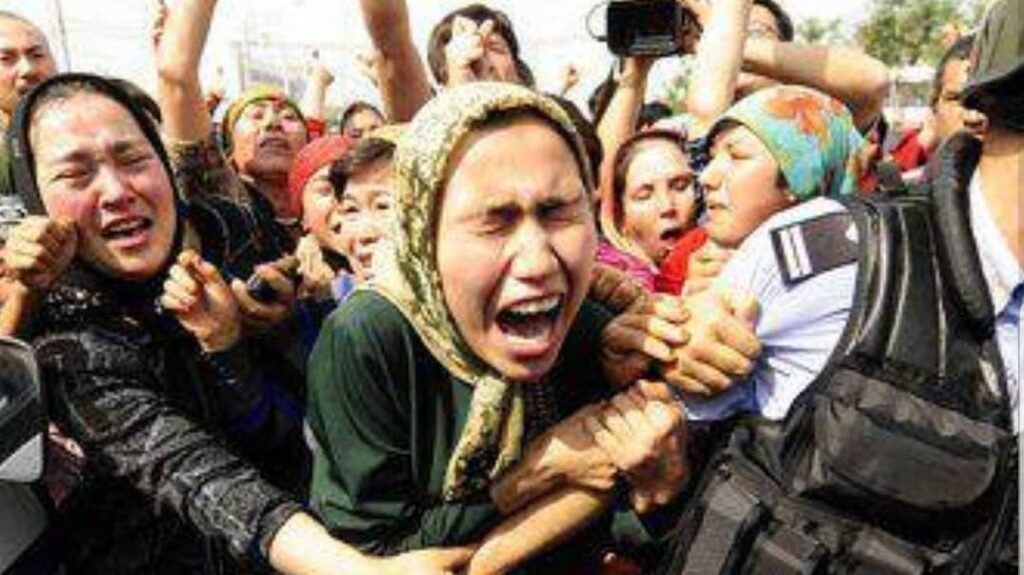

If so, what do we, as a nation or state, have to say about the colossal human rights violation of the Uighur population of the Xinjiang province of China?

Do we condemn outright what is happening there? Or is the matter too sensitive ? Is it, in the view of Iveagh House, unwise to risk the ire of Beijing by taking a position? If Uighurs were predominantly Christian, would we bite our lips rather than officially condemn the savagery of Beijing’s campaign of religious and cultural extinction.

There was a time when the Irish government felt moved to express its concerns about the Chinese treatment of the Tibetans. But that was long,long ago.

When members of the Ireland-Taiwan Parliamentary Friendship Group visited Taipei as observers of their free and entirely democratic presidential and congressional elections in January this year, we did so in the shadow of a controversial warning off by no less a person than the Ceann Comhairle.

Whether his written warning sent to every member of the Dáil and Seanad was inspired by Chinese diplomats in Dublin or just by Iveagh House is not clear. But the message was clear. Irish parliamentarians were advised to avoid engaging with the Taiwan government.

As this paper reported in October 2018, the Ceann Comhairle had written that “active engagement” by Oireachtas members with the Taiwan government was in conflict with Ireland’s “One China” policy and was “a danger to Ireland’s national interest.”

Citing Ireland’s substantial and growing trade with communist China, he went on to disclaim any intention to tell Oireachtas members whom they should or should not meet or what functions they should or should not attend. Heaven forbid! He merely wanted to “remind them” of Ireland’s developing relations with China and the “danger” of such parliamentary contacts to Ireland’s “national interest”.

So there you have it. That is how Ireland’s national interest is to be judged. That is the yardstick by which our international and human rights values are to be judged.

I and other Senators repeatedly called in November and December last year on the Minister for Foreign Affairs to come before the Seanad and debate with us the Irish silence on the Uighurs’ internment in huge concentration camps. Our calls were ignored – presumably “in the national interest”.

The great majority of EU member states have de facto relations with Taiwan, the only part of China where freedom, human rights and democracy continue to exist. The EU has a representative office in Taipei. Ireland has none. And I found on my visit there in January that Ireland mainly ignored the EU office, and that Ireland was an obvious outlier among EU member states most of which maintain their own representative offices there as well.

When Donald Trump attended the G20 conference in Japan in 2019, he told President Xi, according to the awful John Bolton, that he supported the measures against the Uighurs revealed in western media as legitimate steps to counter terrorism.

Trump had earlier told Americans that he had received a “beautiful” letter from President Xi as part of his trade negotiations with China.

“Beautiful” is an adjective that means many things in Trump-speak. He recently told Fox TV viewers that changing the name of Fort Bragg named after a confederate general was wrong because many US soldiers had been stationed there in two world wars, “beautiful world wars… (pause) … that were vicious and horrible”.

Now China is the electoral enemy. Now Joe Biden is painted as the tool of China. A new narrative is emerging that President Xi is not as “beautiful” a correspondent as he was two years ago. The Democrats are now the treacherous allies of President Xi. Trump seems to have forgotten (if indeed he ever knew or understood it) that the US rapprochement with Red China was the brainchild and project of Nixon, Kissinger and, later, of the Bushes.

Let’s see how our UN ambassador deals with the Uighur issue on the UN Security Council. Will our “national interest” allow us to be forthright and truthful for a change? Or will the risk to our trading prospects with China be the cat that catches our tongue.

I remember being told by the late Padraig Ó hUiginn that often there were three phases in how Iveagh House dealt with issues of international controversy – the first when it would be too early to say anything, the second when it would be too sensitive, and the third when it was too late.

Of course, it has since been renamed as the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade.

Will Ireland condemn the cultural genocide of the Uighurs as vocally as we condemned the subjugation and expulsion of the Rohinga by Myanmar with which trading considerations were not such an issue?